This year has seen an influx of OEMs devote resources and time to powertrain electrification – Volvo, Jaguar Land Rover and Aston Martin are just a few. However, this isn’t the first time auto makers have invested in the development of alternative fuel solutions. There is an air of symmetry to the industry as today’s OEMs contemplate a possible future without oil – over 40 years ago the prospect of an unsustainable future for the IC engine was beginning to become apparent and US manufacturers focused their energy on the development of a fully electric powertrain.

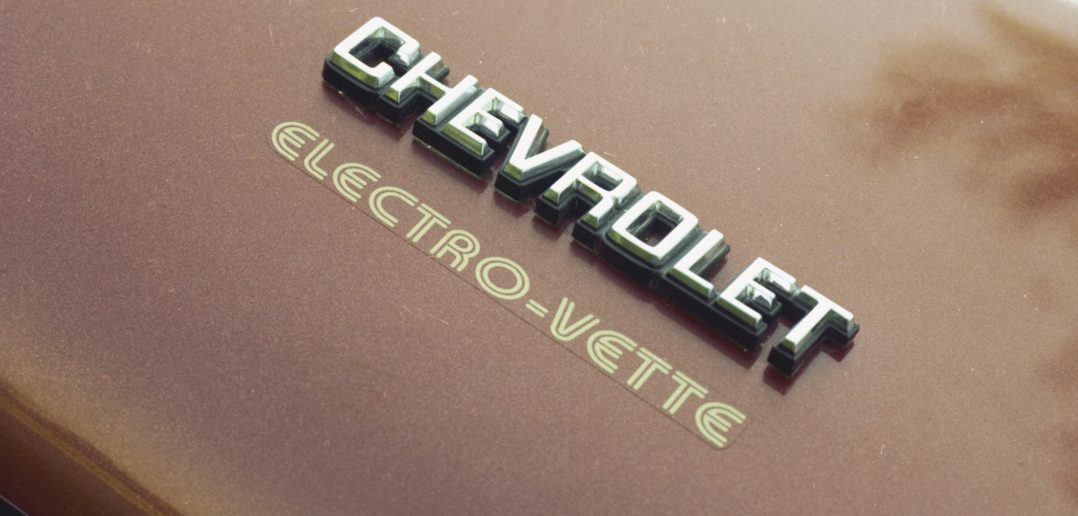

In 1973 a combination of President Nixon’s newly introduced fiscal policy and the USA’s ongoing feud with the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) meant that by the following year oil prices were four times higher than prior to the crisis and the US$2.50 gallon was looking increasingly likely. With the industry sent into panic mode, OEMs rushed to develop alternative fuel solutions for the consumer market and GM introduced the fully electric Chevrolet Electrovette.

Developed by GM’s Advanced Engineering Division and based on the Chevrolet Chevette, the two-door EV featured 20 12V lead-acid batteries and, thanks to a direct current motor and planetary drive, 50kW could be routed to the rear wheels. This meant a top speed of 85km/h (53mph) and 0-48km/h (0-30mph) in 8.2 seconds. But driving at a constant 48km/h would only get you 80km (50 miles) of battery range. In comparison, the 1.6-liter gasoline Chevette – which was in development at the same time and featured the same silhouette – would achieve 7 l/100km (33.6mpg) and hit 159km/h (99mph).

However, the decision to use a DC motor proved pivotal to the future of the EV project. It required carbon conductors and a copper commutator ring which led to friction, arcing and therefore energy loss, affecting what was already a limited range. Though engineers looked into the development of nickel-zinc batteries, which (it was claimed) could double the vehicle’s range, the alternative power source never came to fruition.

A core focus for the project was maximizing the power-to-weight ratio, but despite basing the Electrovette on the smallest car in the country, the retrofitted Chevette compact was no lightweight. With 417kg (920 lb) of batteries replacing the rear seats, the two-passenger prototype weighed 1,338kg (2,950 lb). To combat this, GM worked on lithium and iron sulfide batteries, which would be smaller, lighter and more powerful, but after failing to make a technological breakthrough, the idea was scrapped with an estimated 10 to 15 years of development left to be undertaken.

Despite the experimental nature of the project, GM showed the vehicle publicly at various meetings throughout the USA – and in light of the oil troubles plaguing the country it seemed there was a place in the market for the EV at that time. However, in 1978 the OEM acknowledged the vehicle’s flaws and that a major advance in battery technology was needed. These factors, in combination with the USA soon becoming oil-rich once again, ensured that the Electrovette never received the green light.

Looking at the vehicle now, it’s clear that the powertrain wasn’t the forward-thinking solution that GM intended. However, certain elements hinted at the industry’s future direction. This year GM announced its vision for an all-electric future, starting with two new models in 2018 and followed by a completely electric line-up by 2023.

When Honda unveiled the Urban EV at the 2017 Frankfurt Motor Show there was a sense of the industry coming full circle. With its multispoke wheels, round headlights and retro styling, the concept looked not dissimilar to the Electrovette. The modern reality of finite oil resources means that the automotive industry is once again taking innovative design cues from the past. This time, however, they look like they’re here to stay.