Making batteries safer by understanding the key thermodynamic differences between the most popular cell chemistries

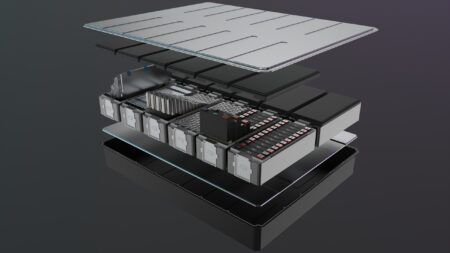

While NMC cells dominate the current generation of US and European BEVs, rising cost pressures are forcing OEMs to take a harder look at LFPs. Despite their lower energy density, LFP cells are still prone to single-cell thermal runaway, and controlling its propagation to adjacent cells remains a top priority. To properly manage thermal runaway propagation (TRP), pack designers must first understand the three key thermodynamic differences between the two cell types.

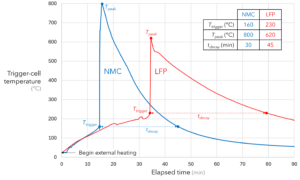

First, NMC cells trigger more easily. The chart below shows two similarly sized prismatic cells triggered into thermal runaway with an external heating pad. The NMC cell goes unstable at a temperature of 160°C, while the LFP holds steady up to 230°C. This deeper thermal well, combined with LFPs’ greater size and weight for the same range, provides an LFP pack with more thermal mass than its NMC counterpart. The thermal mass of adjacent cells is one of the few benign pathways that stray energy can take during a runaway event (the other being rejection through the pack’s cooling system). While cell-to-cell conduction by itself cannot absorb the full brunt of a runaway event, thermal mass can provide additional time for occupants to pull over and get clear of the vehicle.

Second, NMC cells burn hotter than LFPs. Once pushed into thermal runaway, the NMC cell-face temperature peaks at 800°C, while the LFP only spikes to 620°C. This is somewhat paradoxical since, despite their lower energy density, calorimetry shows that LFP cells often have a higher fuel content per amp-hour of storage capacity. However, because NMCs smuggle more elemental oxygen into the cell, their combustion efficiency and, therefore, heat release is higher.

Finally, the ejection phenomena associated with each cell chemistry are very different. When an NMC cell goes into thermal runaway, there tends to be a 10- to 30-second period in which liquid, gas, and solid materials are violently ejected through the cell vent. These solid materials are typically bits of aluminum, carbon, and burning plastic. So NMC cells bring all three elements of the fire triangle – fuel, oxygen, and an ignition source – to a thermal runaway event. The resulting torch-and-grit blast can burn through all but the sturdiest enclosure materials and blankets the surrounding cells in flaming gases and debris. Managing these flows is one of the most difficult aspects of designing a TRP-resistant NMC pack.

In contrast, LFP cells tend to emit mostly smoke and gas which, although hot, is typically not actively combusting. While subsequent combustion and even explosions are possible, the interior of an LFP pack is typically oxygen-starved during a thermal runaway event, so these risks exist primarily outside the vehicle. Further, the total mass ejected from an LFP thermal runaway is only 20-25% of the original cell mass, versus 40-50% for an NMC. So, both the hazard level and quantity of LFP ejecta are lower than that of NMC designs.

In short, controlling thermal propagation in an NMC pack is primarily about gas management and secondarily about direct cell-to-cell heat transfer. In an LFP pack, that dynamic is reversed. This is fortunate: with the advent of aerogel thermal barriers such as PyroThin cell barriers, cell-to-cell heat transfer is now a solved problem. Managing combustion gases and flaming ejecta remains stubbornly hard to address.

aerogel.com